By Joe Hurley, RMIT University; Ebadat Parmehr, RMIT University; Kath Phelan, RMIT University; Marco Amati, RMIT University, and Stephen Livesley, University of Melbourne

Greater recognition of the benefits of urban forests is focusing efforts from all levels of government to defend and improve them.

Perhaps the most iconic of these efforts is New York City’s Million Trees Program. Other initiatives of note include the City of Melbourne’s and the City of Sydney’s.

Earlier this year, federal Environment Minister Greg Hunt declared:

Green cities – cities with high levels of trees, foliage and green spaces – provide enormous benefits to their residents.

Hunt pledged to develop:

… decade-by-decade goals out to 2050 for increased overall tree coverage.

But achieving green cities will need more than just canopy cover targets and central city strategies. In contested urban environments, it will require new approaches to urban planning and development.

Urban development and the urban forest

As cities grow, pressure for urban consolidation increases. Planning policies that enable compact city development, along with increased market demand for smaller, well-located dwellings, contribute to this pressure.

Urban consolidation is an important policy goal to improve cities. While not uncontested, consolidation slows cities’ outward expansion. This can reduce the loss of agricultural and ecologically significant land and provide a more efficient urban form.

Yet, as cities become denser and the traditional suburban “house and garden” is redeveloped, buildings are replacing trees. How is it possible to reconcile urban consolidation with urban greening and increased canopy cover?

A critical first step is to measure the urban forest and assess the impact of redevelopment and consolidation on canopy cover. This should inform strategies to best meet compact city goals while enabling a rich and extensive urban forest. This agenda forms part of the work of the National Environmental Science Program’s Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub.

A case study of the Melbourne suburb of Williamstown illustrates the potential conflict between consolidation and the urban forest.

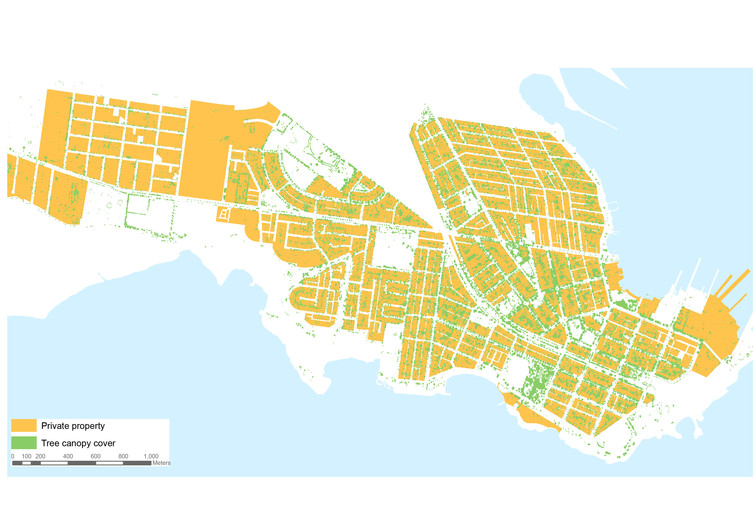

The map below brings together tree canopy cover derived from remote sensing with analysis of land use and zoning. It shows tree canopy cover on both private and public land.

Tree canopy cover and the public/private realm in Williamstown. Author provided

Some 55% of the canopy is over private land. Urban forest policies, which typically focus on the public realm, are at best tackling only half the picture. Urban consolidation policies also rarely note the impact of redevelopment on the urban forest.

Urban deforestation

Tiny backyards in new fringe areas and boundary-to-boundary development in existing suburbs often eliminate private land’s potential contribution to the urban forest. This puts incredible pressure on the public realm to provide the urban forest.

Current land-use policies support dispersed piecemeal redevelopment of individual lots in existing suburbs, which produces relatively few new homes (as below). At the same time, replacing an existing home with a larger house or with several townhouses typically results in all existing vegetation being stripped from the site.

These Preston townhouses are an examples of dispersed, low-yield consolidation. Joe Hurley

Meeting future housing needs in this way would require redevelopment of a vast number of these lots. This would have a significant impact on the urban forest.

Higher-density modes of consolidation also typically eliminate vegetation. However, their greater housing contribution means this form of consolidation’s cumulative impact on the urban forest is significantly less than that of low-density redevelopment (as below).

This apartment building in Hawthorn, Victoria, is an example of higher-density consolidation. Kath Phelan

An urban forest, not a concrete jungle

Compact city land-use policies and urban forest policies need to work together to ensure that cities have high-quality built environments and extensive tree cover. These policies must set the overall goals and outline strategies to deliver on them for both public and private land.

Cities urgently need more strategic identification of small and large lots that are suitable for more intensified development, particularly to reduce the need for the widespread low-level consolidation that threatens tree cover.

Land-use regulation should ensure that both low-yield and higher-density redevelopment maintains the contribution of private land to the urban forest. Existing and new approaches to achieving this outcome need to be considered – whether through local rules, government programs or incentive schemes.

An early leader in this space is Brimbank City Council, which has made modest but important planning scheme changes to require trees in the front yards of two-lot subdivisions.

Rapid urban consolidation will change urban landscapes significantly over the next few decades. The right decisions need to be made now to ensure the consolidation of cities maximises the benefits of redevelopment while also protecting one of their most critical functional, cultural and environmental assets.

![]()

Joe Hurley, Senior Lecturer, Sustainability and Urban Planning, RMIT University; Ebadat Parmehr, Research Officer, School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University; Kath Phelan, Research Fellow, School of Global, Urban Social Studies, RMIT University; Marco Amati, Associate Professor of International Planning, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University, and Stephen Livesley, Senior Lecturer in Urban Biogeochemistry, University of Melbourne

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/API_Property_News/~3/J6MRqcMBRPE/