James Lesh, University of Melbourne

The Australian Ugliness, architect and critic Robin Boyd wrote in 1960, incorporated the “background ugliness” of Australia’s cities: a suburbia of:

… unloved veneer villas and wanton little shops, and big worried factories.

These are the kinds of suburban places that in 2016 sell at weekend real estate auctions for six or seven figures. Despite the frequent outcries of today’s residents of “Trendyville”, these buildings are readily converted to fashionable heritage homes, or demolished to make way for new apartment blocks.

Heritage has a history. The kinds of things and places that Australians have preserved and the ways they have gone about preserving them have expanded in recent decades.

This heritage exists not only in museums and galleries or at historic properties and CBD buildings. It also forms part of our everyday urban experiences: located in suburbs and neighbourhoods, along and between streets, among current and former factories, stores, pubs and homes.

Finding Trendyville

A place where this heritage history has played out dramatically has been in the inner suburbs of the Australian city.

Why call this place Trendyville? Without a conventional gentry, the term gentrification is arguably historically inappropriate for Australia. So we might instead consider gentrification as trendification, the inner suburbs as Trendyville, and the residents as trendies.

The trendies arrived in the late 1960s. Like hipsters today, few people considered themselves a trendy, except perhaps ironically. More commonly, a trendy was identified by another person based on dress, clothing and shopping bags.

For urban historians Renate Howe, David Nichols and Graeme Davison, Trendyville evokes:

… the junction between geography, culture and politics, on the road between memory and history.

The city of memory is a productive way of thinking about urban heritage. It is also a powerful way of tackling the relationship between cities, people and history.

‘Trendies’, Greville Street, Prahran, Melbourne, 1973. State Library of Victoria

Before Trendyville

Until the mid-to-late 20th century, the Australian inner suburbs – New Farm and Subiaco, Carlton and Glebe – were not the desirable places of today.

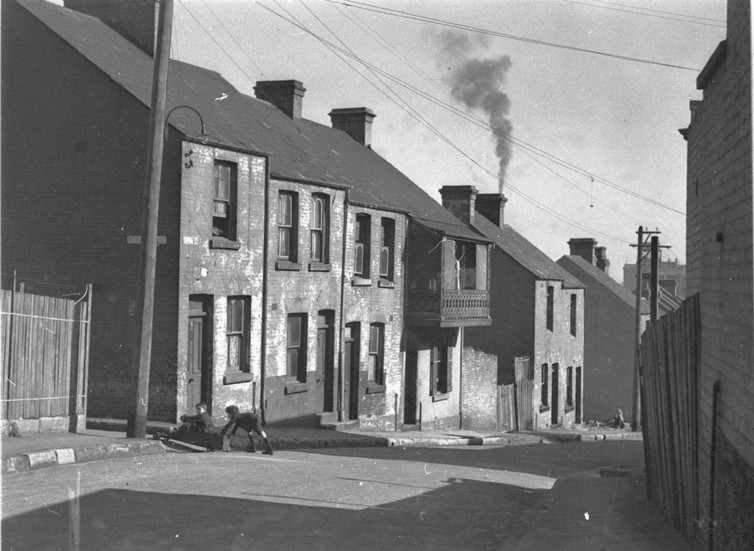

The houses, terraces, villas, cottages and other buildings that lined the streets of Trendyville had been built in the 19th and early 20th century. By the post-war period, many of these buildings had become run down, perceived as both unsustainable and contrary to social progress: in need of urban renewal.

Surry Hills and Redfern, Sydney, ca. 1930s. State Library of NSW

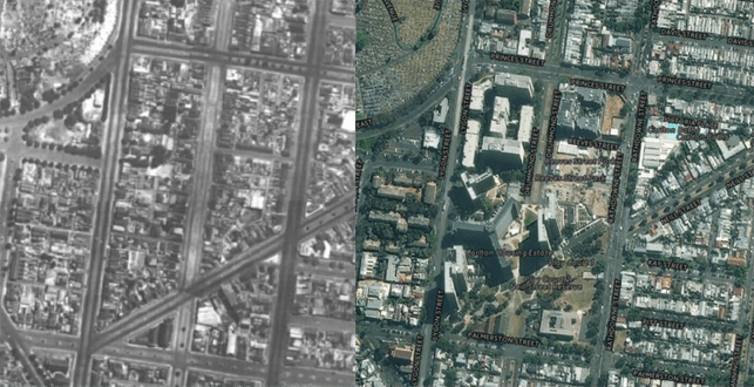

These rings included a CBD core for commercial activities, an underdeveloped inner circle, and an aspirational outer suburban circle. Post-war urban planners thought the emptying out of the inner-city – “the doughnut effect” – was inevitable.

The residential suburbs of the inner circle were identified as transitional zones, assuming that aspiring residents would eventually seek out the outer suburbs. Urbanists designated these seemingly dilapidated areas as slums, to be cleared for comprehensive modern redevelopment.

Aerial view of Carlton, Melbourne before and after Housing Commission of Victoria high-rise flats, 1945 and today. www.1945.melbourne

High-rise social housing schemes were built, inspired by French architect Le Corbusier. The results of these policies include the Brutalist Sirius Apartments in Sydney and the 1960s high-rise housing that circles inner Melbourne.

Sirius Apartments from Circular Quay, Sydney, 2014. hpeterswald/Wikimedia

Heritage in Trendyville

From the 1960s, the backlash against these inner-suburban clearances was led by the trendies. Not everyone was enraptured by the “white-picket fence” suburban ideal. Following southern and eastern European migrants, students and middle-class professionals moved to the inner suburbs. Other people had never left, witnessing the demolitions around them.

Resident protest, Brisbane. 1970. Brisbane City Council

The union-imposed “green bans” – at places like the Rocks and Woolloomooloo, South Melbourne and Collingwood, Highbury Park, and Fremantle – was another powerful way to intensify this heritage advocacy.

Resident protest, Woolloomooloo, Sydney, ca. 1973. City of Sydney Archives

The trendies transformed Boyd’s “background ugliness” into heritage that warranted preservation. Australia’s residential vernacular, its neighbourhoods, streets and homes, were looked upon with increasing fondness. This occurred amid a shifting mentality toward community building, the environment, sustainability and local amenity.

Drawing on urbanists such as North American Jane Jacobs, heritage preservation became an aspect of community-making. The resident action groups brought people together, and the green bans helped people to claim their right to the city.

Trendyville’s troubles

From the 1970s, Trendyville became subject to new heritage laws, which sought to preserve its “historic character”.

Although these heritage protections were in part intended to give residents a greater say, those responsible for making the assessments were nevertheless heritage experts, often distanced from the communities.

Catherine Street, Subiaco, Perth, 1984. State Library of Western Australia

The trendies had arrived at a time when the inner suburbs were still perceived as in decline. The heritage protections had been implemented in response to their aesthetic and historical sensibilities.

Today, those heritage protections envelope large and sought-after areas of the inner city. With Australia’s population booming, urbanists advocate for greater density. More people will need to live in existing suburbs to make our cities sustainable.

Former Tip Top Bakeries, Brunswick East, Melbourne, 2014. Little Projects

What it means to meaningfully preserve Trendyville’s heritage, Australian inner-suburbia, must be rethought for the 21st century.

After all, as illustrated by recent calls to preserve Sydney’s Sirius Apartments (which were once opposed by heritage advocates) our understandings of heritage are always shifting.

![]()

James Lesh, PhD Candidate, School of Historical and Philosophical Studies and Melbourne School of Design, University of Melbourne

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/API_Property_News/~3/I1iuehptHJk/